Trauma During the Early Years

Common types of childhood trauma:

- Psychological, physical or sexual abuse

- Neglect

- Family or community violence

- Serious accidents or life-threatening illness

- Natural disasters

- Loss or separation from a loved one

- Forced displacement or war experiences

- Serious and untreated parental mental illness

- Discrimination

- Persistent extreme poverty

Source: “How to Implement Trauma-informed Care to Build Resilience to Childhood Trauma” by Jessica Bartlett and Kate Steber

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and toxic stress during the early years

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) refer to negative, stressful and traumatic events that a child may experience or witness during childhood. Examples of Adverse Childhood Experiences include physical or emotional abuse, chronic neglect, caregiver substance use or mental health challenges, exposure to violence, and persistent family economic hardship.

When a child experiences frequent and/or prolonged adversity without the support of caring adults, they can experience what is known as ‘toxic stress’. Toxic stress is the excessive activation of stress response systems in the body and brain. Toxic stress weakens the foundation of a child’s developing brain, which can lead to lifelong problems in learning, behaviour, and physical and mental health.

Common reactions to trauma in babies and toddlers

When babies or toddlers are exposed to traumatic events, they become very scared – just like anybody else. Some common reactions may include:

- unusually high levels of distress when separated from their parent or primary caregiver

- a kind of ‘frozen watchfulness’ – the child may have a ‘shocked’ look

- giving the appearance of being numb and not showing their feelings or seeming a bit ‘cut off’ from what is happening around them

- loss of playful behaviour

- loss of eating skills

- avoiding eye contact

- being more unsettled and much more difficult to soothe

- slipping back in their physical skills such as sitting, crawling or walking and appearing more clumsy

Three Kinds of Responses to Stress

Positive stress

Positive stress results from adverse experiences that are short-lived and is characterized by brief activation of the body’s alert systems. Brief increases in heart rate and hormone levels are signs of positive stress. Children may experience positive stress when they attend a new school, visit the dentist or meet someone new. This type of stress is considered normal and coping with it is an important part of the development process.

Tolerable stress

Tolerable stress refers to more intense adverse experiences that activate the body’s alert systems to a greater degree. Examples of tolerable stress include a frightening natural disaster or the death of a loved one. If the stress response is time-limited and buffered by relationships with caring adults who help the child adapt, the child’s brain and other organs recover from what might otherwise be damaging effects.

Toxic stress

When a child experiences frequent and/or prolonged adversity without the support of caring adults, they can experience what is known as ‘toxic stress’. Toxic stress is the excessive activation of stress response systems in the body and brain. Toxic stress weakens the foundation of a child’s developing brain, which can lead to lifelong problems in learning, behaviour, and physical and mental health.

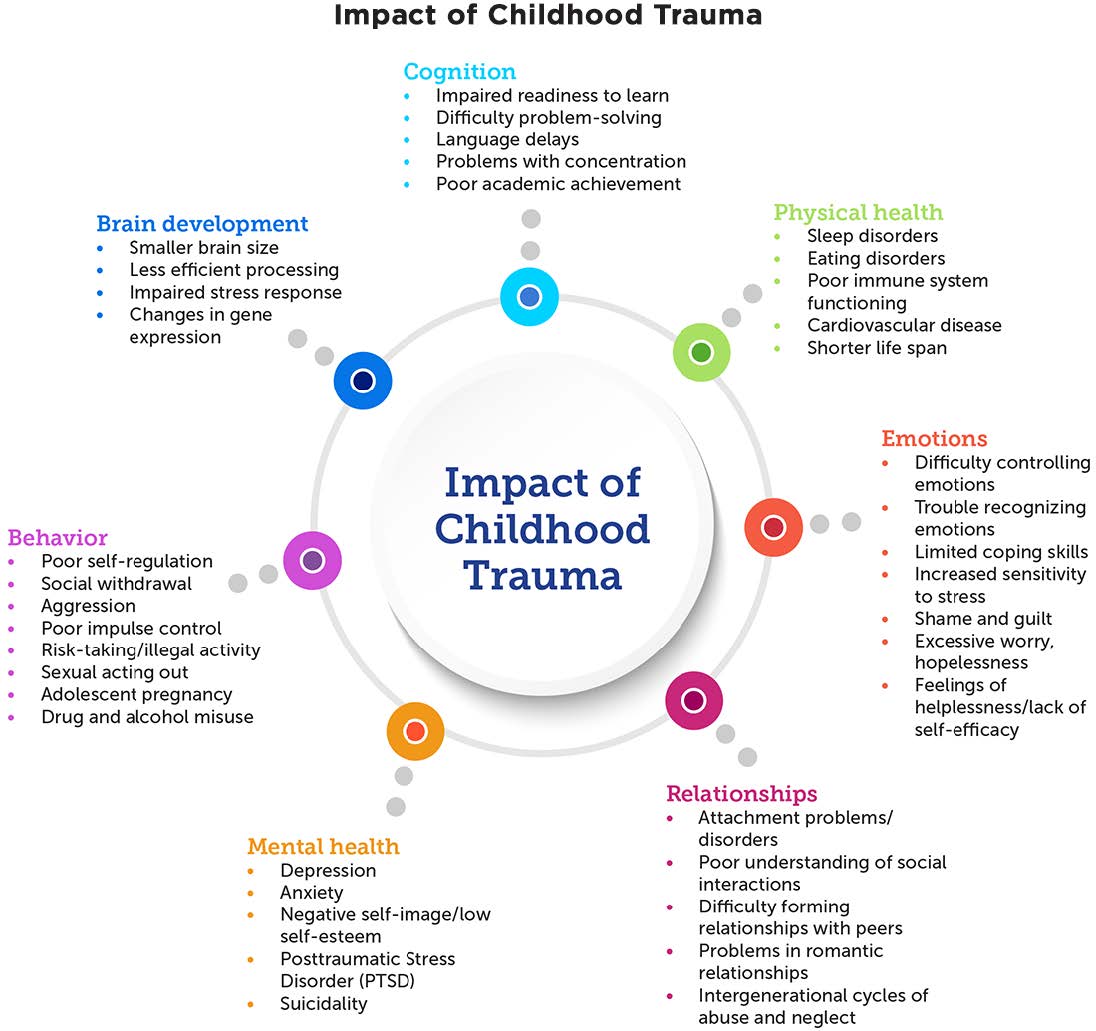

How Early Childhood Experiences Affect Lifelong Health

Trauma and children in foster care

Every child in foster care has experienced trauma. Not only do they suffer trauma from the circumstances that led to foster care in the first place, but they also experience trauma when they are separated from their parents, community and culture. At any age, it is traumatic for a child when they are removed from their home, family, familiar faces and neighbourhood. It is widely accepted that skin-to-skin contact between parents and their babies has significant health benefits for the infant. Physical contact and proximity to their parents is therefore crucial during a child’s early years. Attachment theory suggests that emotional distress and later health problems can be attributed to early childhood disruption of the parent-child bonding process.

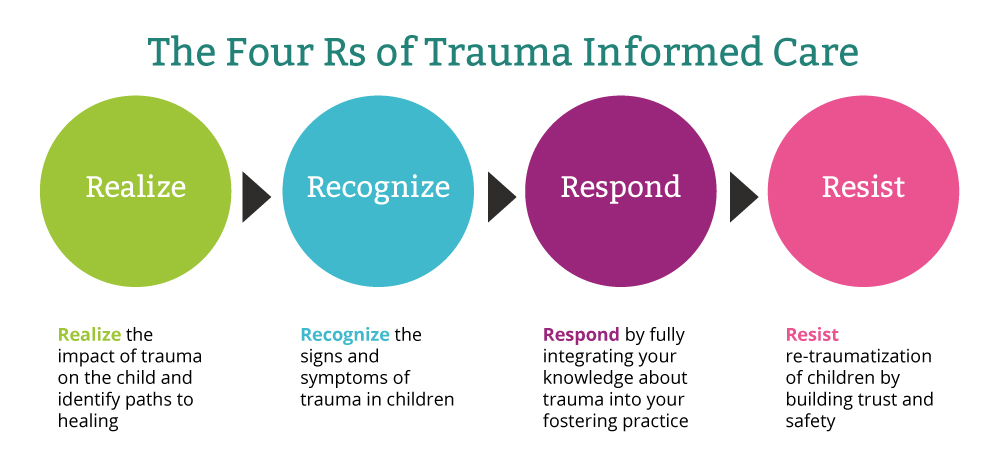

The goal of caregivers should be to restore a child’s sense of safety and comfort. When children temporarily cannot live with their own family, foster caregivers step in and create a safe, secure and nurturing environment that responds to the child’s individual needs. Fostering children means helping them maintain contact with their family, community and culture with a view to reunification with their families or permanency. By understanding trauma, foster parents can help support a child’s healing, the parent-child relationship, and their family. A child’s recovery from trauma rests on having a supportive caregiving system, access to support, and service systems that are trauma-informed.

This figure is adapted from: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and Guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS publication no. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Quiz time!

Take this quick knowledge check about trauma and early childhood development.

References

A guide to toxic stress. (2020, January 6). Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/guide/a-guide-to-toxic-stress/

Bruskas, D. (2008). Children in Foster Care: a Vulnerable Population at Risk. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 21(2), 70-77.

Doyle, J. J. (2007). Child protection and child outcomes: Measuring the effects of foster care. The American Economic Review, 96(5 ), 1583-1610.

Isquith, P., Maerlender, A., Racusin, R., Sengupta, A., & Straus, M. (2005). Psychosocial Treatment of Children in Foster Care: A review. Community Mental Health Journal 41(2), 199-221.

Lawrence, C., Carlson, E., & Egeland, B. (2006). The impact of foster care on development. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 57-76.

Neufeld, G., & Maté, G. (2004). Hold on to your kids: Why parents matter. Toronto: A.A. Knopf Canada.

Siegel, D. J., & Bryson, T. P. (2020). The power of showing up: How parental presence shapes who our kids become and how their brains get wired.

Siegel, D. J., & Bryson, P. H. D. T. P. (2012). The whole-brain child. Random House.

What are ACEs? And how do they relate to toxic stress? (2020, October 30). Retrieved from https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/aces-and-toxic-stress-frequently-asked-questions/

Phone

Main:

604-544-1110

Toll-Free Foster Parent Line:

1-800-663-9999

Office hours: 8:30 am - 4:00 pm, Monday to Friday

PROVINCIAL CENTRALIZED SCREENING

Foster parents are encouraged to call this number in the event of an EMERGENCY or CRISIS occurring after regular office hours:

1-800-663-9122

REPORT CHILD ABUSE

If you think a child or youth under 19 years of age is being abused or neglected, you have the legal duty to report your concern to a child welfare worker. Phone 1-800-663-9122 at any time of the day or night. Visit the Government of BC website for more info.

address

BCFPA Provincial Office

Suite 208 - 20641 Logan Avenue

Langley, BC V3A 7R3

contact us

Fill out our contact form...

News

Site menu

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Charitable Registration #

106778079 RR 0001

Our work takes place on the traditional and unceded Coast Salish territories of the Kwantlen, Katzie, Matsqui and Semiahmoo First Nations. BCFPA is committed to reconciliation with all Indigenous communities, and creating a space where we listen, learn and grow together.

© 2021 BC Foster Parents. Site design by Mighty Sparrow Design.