Indian Act

The Indian Act is the primary law through which the federal government administers Indian status, local First Nations governments and the management of reserve land. It gives the government sweeping powers to control most aspects of Indigenous peoples’ life: Indian status, land, resources, education, and political structures.

The Indian Act pertains to people with Indian status and does not apply to Métis, Inuit, and non-status First Nations peoples. A person who is Status meets the definition of an Indian under the Indian Act and has certain rights and restrictions. The rights include:

the granting of reserves and the rights associated with them

an extended hunting season

a less restricted right to bear arms

some medical coverage

more freedom in the management of gaming and tobacco

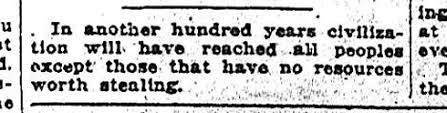

It is important to note that “Indian” is a legal word that many Indigenous peoples are not comfortable using to describe themselves. The earlier versions of the Indian Act evidently aimed to assimilate First Nations. It also made enfranchisement legally compulsory. People who earned a university degree would automatically lose their Indian status, as would status women who married non-status men. Women also lost their status if their husbands died or abandoned them in which case they lose the right to live on reserve land and have access to band resources. Some traditional cultural practices were also prohibited. These discriminatory policies have had lasting negative impacts on generations of Indigenous peoples. The Indian Act is still in force today and is administered by Indigenous Services Canada. Despite amendments, the Indian Act continues to be heavily criticized.

Indian Act Timeline

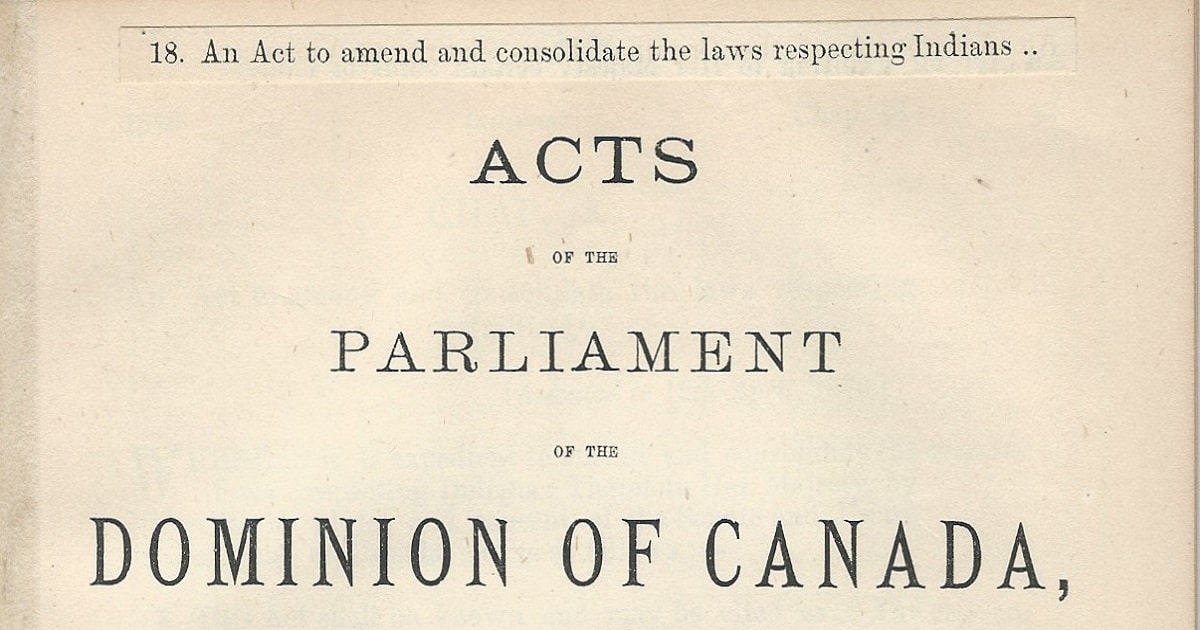

1876

The Indian Act is created. Any existing Indigenous self-government structures are extinguished. It replaced traditional structures of governance with band council elections. Hereditary chiefs — leaders who acquire power through descent rather than an election — are not recognized by the Indian Act.

An Indian is defined as “any male person of Indian blood” and their children. Provisions include: status women who marry non-status men lose status; non-status women who marry status men gain status and anyone with status who earns a degree or becomes a doctor, lawyer or clergyman is also enfranchised.

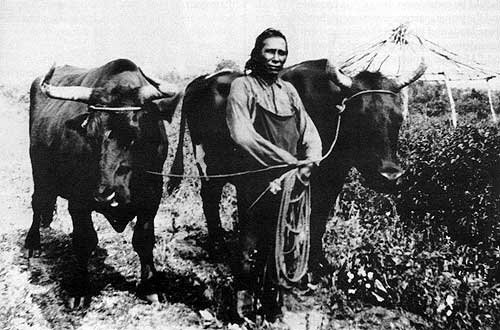

1880

Indigenous farmers are expected to have a permit to sell goods such as cattle, grain, hay or produce. They must also have a permit to buy groceries and clothes.

1884

Attendance in residential schools becomes mandatory for status Indians until they turn 16. Children are forcibly removed and separated from their families and are not allowed to practice their culture or speak their own language. The sale of alcohol is also prohibited.

1885

Through an amendment to the Indian Act, Indigenous peoples are prohibited from conducting their traditional Indian ceremonies such as the potlatch, ghost dance, and sun dance. A pass system is also created and Indigenous peoples are restricted from leaving their reserve without permission.

1886

The definition of Indian is expanded to include “any person who is reputed to belong to a particular band or who follows the Indian mode of life, or any child of such person.” Voluntary enfranchisement is allowed for anyone who is “of good moral character” and “temperate in his or her habits”.

1914

An amendment prohibits dancing off-reserve. First Nations peoples are also required to ask for permission before wearing any traditional and ceremonial clothing at public events.

1918

The government gives itself the power to take reserve land from bands without their consent. They could also lease out land to settlers without the band’s agreement.

1927

Status Indians are barred from seeking legal advice, fundraising, or meeting in groups.

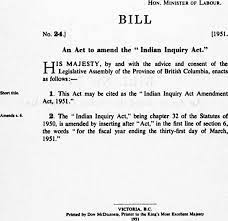

1951

Amendments to the Indian Act remove some of the most offensive political, cultural and religious restrictions. Political organizing and cultural activities are allowed.

1960

First Nations peoples are finally allowed to vote in federal elections. They could now vote without losing their status.

1961

Compulsory enfranchisement is removed.

1985

Bill C-31 was passed, amending the Indian Act to align with gender equality under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. This addresses gender discrimination in the Indian Act and restores Indian status to those who had been enfranchised against their will. The amendment also allows First Nations to control their own membership as a step toward self-government.

1996

The federal government proposed Bill C-79 to amend areas of the Act including band governance and the regulation of reserves. The majority of First Nations were opposed to Bill C-79 because they were not consulted. Bill C-79 failed to become law.

2002

Bill C-7, also known as the First Nations Governance Act, sought to give band councils more power in terms of governance but it ultimately failed.

2010

The federal government announced its intent to work with Indigenous peoples to remove part of the Indian Act that gives the authority to create residential schools and remove children from their homes.

2011

Bill C-3, also known as the Gender Equity in Indian Registration Act, was passed. It was a response to Sharon McIvor’s gender discrimination case against the government. Sharon gained her status when Bill C-31 was passed. However, she was not able to pass on those rights to her descendants in the same way that a man with status could. Bill C-3 grants status to grandchildren of women who regained status in 1985. However, the descendants of women, specifically in terms of great-grandchildren, did not have the same entitlements as descendants of men in similar circumstances. Therefore, Bill C-3 still denied status rights to some individuals because of gender discrimination.

Learn more about The Indian Act and listen to this episode of The Secret Life of Canada, hosted and written by Falen Johnson and Leah Simone Bowen.

References

Gray Smith, M. (2017). Speaking Our Truth: A Journey of Reconciliation. Orca Book Publishers.

Joseph, B. (2018). 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act: Helping Canadians Make Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples a Reality. Indigenous Relations Press.

The Indian Act. (n.d.). Welcome to Indigenous Foundations. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/the_indian_act/

Indian status. (n.d.). Welcome to Indigenous Foundations. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/indian_status/

Phone

Main:

604-544-1110

Toll-Free Foster Parent Line:

1-800-663-9999

Office hours: 8:30 am - 4:00 pm, Monday to Friday

PROVINCIAL CENTRALIZED SCREENING

Foster parents are encouraged to call this number in the event of an EMERGENCY or CRISIS occurring after regular office hours:

1-800-663-9122

REPORT CHILD ABUSE

If you think a child or youth under 19 years of age is being abused or neglected, you have the legal duty to report your concern to a child welfare worker. Phone 1-800-663-9122 at any time of the day or night. Visit the Government of BC website for more info.

address

BCFPA Provincial Office

Suite 208 - 20641 Logan Avenue

Langley, BC V3A 7R3

contact us

Fill out our contact form...

News

Site menu

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Charitable Registration #

106778079 RR 0001

Our work takes place on the traditional and unceded Coast Salish territories of the Kwantlen, Katzie, Matsqui and Semiahmoo First Nations. BCFPA is committed to reconciliation with all Indigenous communities, and creating a space where we listen, learn and grow together.

© 2021 BC Foster Parents. Site design by Mighty Sparrow Design.